Political Cartoons and Protest Art in Modern Africa

Let’s be honest—some of the most fearless voices shaping Africa today aren’t politicians or journalists. They’re the artists.

Protest artists. Cartoonists. Visual rebels armed with brushes, spray cans, and tablets. These creators aren’t trying to be polite. They exist to stir the pot. To spark debate. To say what many are afraid to say.

From Khartoum to Lagos, you will find their works everywhere—on walls, on screens, in the streets, in WhatsApp groups, and even in daily newspapers and magazines. They don’t just make art; they create mind-boggling statements. They tackle police brutality, bad governance, gender inequality, and corruption with a mix of anger and creativity. And they do it too—with sharp, unfiltered, unapologetic humour.

This art doesn’t wait for permission. It doesn’t ask for approval. It just shows up, loud and unbothered. It gets shared, liked, reposted, and talked about. That’s the power of protest art in Africa at the moment—and it’s only getting stronger.

Let’s dive in.

Sudan’s Walls: More Than Just A Painting

In 2019, Sudan exploded with protest energy. And while people marched and chanted in the streets, artists picked up their brushes. Murals flooded Khartoum—big, bold, and fearless.

One artist, Alaa Satir, became a voice for women in the revolution. Her murals weren’t just pretty. They were fierce. They screamed things like, “We are the revolution.” And people listened. These walls weren’t just covered in paint—they were covered in power.

Sudan’s street art turned into some kind of a public protest journal. Every mural captured a feeling, a moment, a demand. And guess what? People still go back to those walls. They still remember what they stood for.

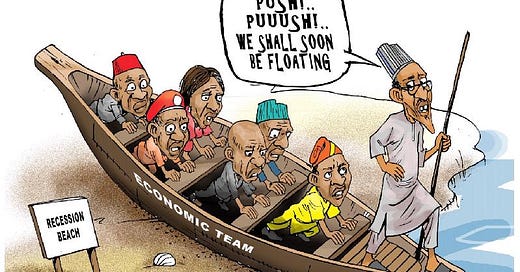

Nigeria: Cartoons That Bite

When Nigeria’s #EndSARS protests swept the nation, political cartoons became weapons. And one of the sharpest pens in the game? Mike Asukwo.

Asukwo’s style is unmistakable—clean, detailed, and brutally honest. His caricatures expose corruption, bad leadership, and social hypocrisy. One cartoon might show a politician sitting on bags of rice meant for flood victims. Another might highlight the silence of lawmakers during a crisis.

He doesn’t miss. And he doesn’t hold back. Asukwo, along with others like Tayo Fatunla, helped shape how Nigerians processed their rage during times of national tension. Through exaggeration and satire, they said what many couldn't.

South Africa’s Sharpest Pens

South Africa’s protest art roots run deep. During apartheid, posters were printed in secret. Artists smuggled them into towns as acts of resistance.

Today, the tradition continues with voices like Zapiro—arguably South Africa’s most fearless cartoonist. His work is direct, controversial, and unapologetically political. His cartoon “Rape of Lady Justice” was explosive. His critics called it too far. Supporters called it necessary.

And then there was “The Spear.” A painting of President Zuma, completely exposed, that sparked a nationwide firestorm about art, respect, and freedom of expression. In South Africa, political art isn’t just commentary. It’s a cultural event.

Why This Art Medium Matters

The reality is that most people don’t read policy reports. But a cartoon of a president dressed as a clown? Everyone remembers that. A mural of a protester with wings? That image lasts longer than a headline.

Protest art is fast, visual, and emotional. It bypasses jargon and gets straight to the point. It simplifies big issues—corruption, violence, poverty—and turns them into moments of clarity.

The Future Is Bold and Digital

Social media has turned protest art into a movement. One sketch can go global in minutes. New voices are emerging, combining animation, memes, and traditional art to build the next generation of protest visuals.

Whether it’s Mike Asukwo posting to X (formerly Twitter) or a teenager spray-painting slogans on a street in Kinshasa, the message is clear: Africa’s artists are not silent.

And they are here to stay.